If Oxytocin induces an approach-oriented profile, what does that mean for society?

By Alondra De Lahongrais Lamboy AGMU’26 and Jim Stellar

According to a study, oxytocin administration induces an “approach-oriented cardiovascular profile” during stressful situations. We find that statement very interesting especially in light of the role for vagus input from the heart and other organs to the brain in cognition and in stress.

Classically oxytocin is well-known to be a hormone that induces generosity, affiliation, and other prosocial behaviors in people, and as Paul Zak says, the best way to release oxytocin in another human being (outside of nursing in mothers) is to give a welcome hug. The presence of oxytocin promotes positive social interactions and may ultimately improve established dynamics between individuals.

We see wide applications as seen in AL’s past undergraduate research work reviewing literature on training programs for psychosocial support for cancer patients and caregivers who are experiencing emotional distress. The better we understand how these processes work, the better we can hope to meet their needs in a public health manner. Mental health remains a stigmatized area in cancer care, with patients commonly feeling overwhelmed by the physical symptoms of cancer, making it difficult for them to acknowledge the mental and emotional toll the illness takes.

Looking at factors that affect patients’ overall functioning is crucial, and in the context of cancer care, oxytocin may play a role in the acceptance of the diagnosis for patients and their communities, which may result in effective adherence to treatment. Examining how oxytocin manifests in the brain may allow us to observe how patients navigate their illness, how that exists within the bigger context of public health, and how we can potentially help. These are the kinds of issues we want to discuss in this blog post and we see them as yet another form of cognitive-emotional integration that generally characterizes this blog series.

But first, what is oxytocin?

Oxytocin

In nursing oxytocin is a hormone made in the brain in the hypothalamus and released into the blood by the pituitary gland. It is triggered by the tactile input of the baby suckling at the mother’s breast. It causes a smooth muscle contraction in the breast that expels the milk into the vestibule of the breast where the baby can draw it out. It is a two-organism reflex that is present in all mammals and allows nursing to be effective. While it has many other effects physiologically and behaviorally, one of the important behavioral ones here is that it promotes social bonding between the mother and baby. That bonding effect produces increased generosity and as discussed by Paul Zak in his TED talk (and as discussed), one good way to release oxytocin in another human is to give them a welcome hug.

So, if oxytocin promotes generosity, why don’t we put it in the water supply of a community, perhaps a university, to make it more collegial by making the participants more generous with each other? Aside from the fact that it is immoral to give people drugs without their knowing it, there is a problem. That problem goes back to the evolution of the group-basis of early human society, where we presumably evolved some of the brain mechanisms we have today. For example, while oxytocin is released naturally by nursing or giving welcome hugs and it promotes intra-group generosity, it also produces inter-group aggression. Why would that be? Well the biggest competitor of our group for food and territory, is likely to be another human group. They want to farm where we do, live where we do, hunt what we hunt and so on. Given that, our strong cohesive early human group had better defend itself.

It remains an open question as to whether the presence of another group stimulates in-group solidarity behavior by being a threat. Think about a football game between two university teams. Does our side chant and cheer good things about their team? Or do we “boo” or otherwise chant bad things about the other team? If we had oxytocin in our water, maybe we would also be more cohesive in fighting with the members of the other university. Now, if we all saw ourselves as on the same basic human team, maybe that would not occur, but inter-group conflict is likely an unfortunate outcome of promoting intra-group cohesiveness by exploiting this oxytocin brain mechanism.

As mentioned above, oxytocin is recognized as a hormone that produces positive feelings, often being referred to as the “love hormone.” To go a bit biological for a moment, a review shows that oxytocin is made in small brain areas in the hypothalamus and sent to the pituitary where it is held for release into the bloodstream. Its actions upon release range from the modulation of neuroendocrine reflexes such as milk let-down in nursing and uterine contractions in childhood to the establishment of complex social and bonding behaviors related to the care of the offspring.

To go more psychological, you may wonder what enables oxytocin to produce effects on social behavior, and it all comes back to its role in the brain. This hormone also manifests itself directly in the brain, in regions like the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus which are involved in emotional regulation processes, social cognition and reward processing. In studies, where oxytocin is tested for its effects on increasing trust, empathy, and bonding levels. For example, In 2008, again Paul Zak and his colleagues tested if the approach of strangers who gave positive signals stimulates the release of oxytocin in others, and if that oxytocin production would be affected by, and affect, social behaviors in humans. To study the role of oxytocin in trust, they had subjects play what is called the trust game. In the trust game, test subjects can signal that they trust a stranger by sacrificing their own money and transferring it to the stranger, who they believe will reciprocate and return more money back to them. Zak and his team found that receiving a signal of trust led to a rise in oxytocin in the blood, an indication of greater production by the brain. They also found that oxytocin caused an increase both in trust and in trustworthy behavior. Oxytocin release occurred only in those who had received a trust signal, showing that oxytocin release happens only when individuals have had social contact with others. Zak refers to positive social signals and interactions as flipping a switch to an “on” state, where the human brain acknowledges a person as safe to interact with.

Oxytocin release and its implications

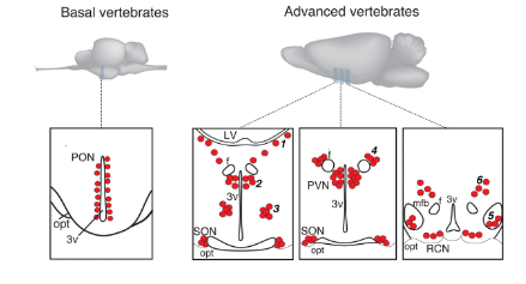

Oxytocin has been a major topic of study in the brain as a hormone and as a neurotransmitter signaling between neurons. If we look deeper into how oxytocin manifests itself in the brain and the way it reaches specific brain regions, we can better understand the complex process it engages in. As we know, oxytocin is produced in small areas of the hypothalamus, specifically in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei, and sent to the pituitary gland where it is stored for release into the bloodstream, or released directly within the brain by neurons as part of its mechanism for control. Oxytocin is then triggered for release in the brain by specific stimuli, like stress or social interactions. It has a well-documented evolution from a 2014 review paper including an expansion of hypothalamic origins in more advanced animals from nuclei around the third ventricle (3v) to other nuclei in hypothalamus as shown in their figure 1, below taken from that paper.

This expansion also occurred in the projections of the oxytocin neurons. For our purposes the important part is the recently evolved connections to the forebrain even in basic laboratory animal subjects for much of neuroscience – the rodent. In the forebrain, oxytocin could alter cognitive operations (as discussed below), just like it could cause smooth muscle contraction when released into the blood as discussed above, where it could also get to forebrain sites if it can enter the brain through the blood-brain barrier.

When oxytocin is released within the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus, it diffuses into the extracellular fluid and influences various brain regions, contributing to its impact on behavior and emotional states. Studies show that oxytocin might potentially enhance interpersonal and individual well-being, and might have more applications in neuropsychiatric disorders, especially those characterized by persistent fear, repetitive behavior, reduced trust, and avoidance of social interactions. Neurobehavioral evidence highlights a possible mediational role for oxytocin. For example, oxytocin, linked to pair bonding and maternal behavior, may function to inhibit anxiety and, at the same time, facilitate affiliative behaviors and bonding. We know that stress, and particularly early life stress, negatively affects affiliative behaviors. Further research suggests that hormones such as oxytocin regulate the cortisol stress response, thereby inhibiting self-preservative behavior associated with fight-or-flight motivation. In addition, experimental studies suggest that oxytocin is related to the onset of maternal behavior and other forms of pair bonding altruism that could be useful in reducing fight-or-flight motivation.

The Approach Oriented Profile

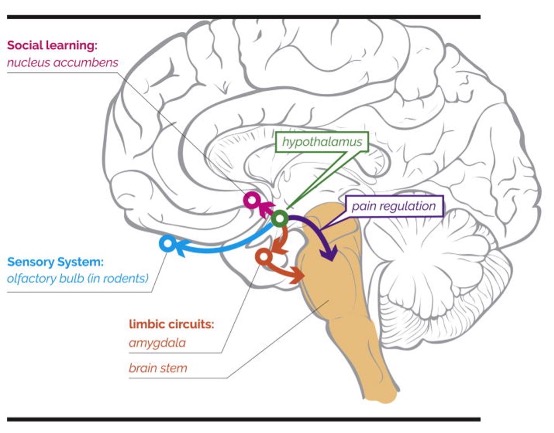

Oxytocin is considered a societal-promoting hormone, and has proven to induce an approach-oriented profile. As a neurotransmitter, it has wide-spread connections to brain areas involved with social learning as shown in the figure below taken from that reference.

Pre-clinical research on the neurobiology underlying social bonding and engagement suggests that oxytocin facilitates bonding and approach behaviors partly by inhibiting stress-related maladaptive cognitive, affective, and biological activation. Its presence in an individual’s body has the ability to not only help them respond better in social settings, it also makes them feel more inclined to even engage in these social interactions. Oxytocin enhances biological readiness to approach or engage in social interaction under stressful conditions. This is one of the many reasons as to why oxytocin is a promising “drug”. In respect to promoting positive social interactions, it has the potential of impacting individuals in a unique way that could ultimately impact society as a whole.

Even though the majority of our knowledge on oxytocin’s regulation of social interactions is based on animal studies, research suggests similar social and stress-related effects in humans. Recent studies suggest that oxytocin plays a role in modulating social perception, recognition, and behavior in human subjects from the amygdala to the prefrontal cortex. That finding concurs with the animal research that emphasizes its role as a biological basis of prosocial approach behavior in humans. Continuing from that study, oxytocin increases an individual’s willingness to accept social risks, which reinforces the belief that it promotes social approach and affiliation. So, when we say oxytocin induces an “approach-oriented profile“, we mean it quite literally; oxytocin increases our desire to approach others, making us engage in social interactions with reduced stress and enhanced emotional recognition, essentially enhancing our social interactions. As a result, an approach oriented profile not only entails increased social interactions, it has the potential to ensure we have meaningful ones.

What does oxytocin do to the brain to create the approach-oriented profile?

In rats, OT receptors are highly expressed in different brain regions, like the olfactory and hypothalamic regions, the amygdala, the thalamus, basal ganglia, and brainstem. However, OT binding sites in humans are not fully understood. Preliminary results suggest that OT receptor distribution in the human brain differs substantially from other species with higher densities in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and the cholinergic nucleus basalis of Meynert.

Animal and human behavioral studies consistently highlight the anxiolytic effects of OT. An initial fMRI study found that intranasal administration of OT decreased amygdala reactivity to negative social cues and reduced functional coupling of the amygdala with brainstem regions. These findings are consistent with recent findings from animal studies indicating that OT decreases behavioral fear responses by modulating amygdala signaling to brainstem regions.

OT seems to dampen neural reactivity to social threats, which may contribute to its anxiolytic effects. Research has found that these effects point to a broader mechanism of decreased vigilance towards social events. Moreover, there may be sex-driven differences in social processing influenced by OT. The effects of exogenous OT may be different depending on individuals’ endogenous OT levels, which can lead to opposing effects on amygdala reactivity in healthy men and women.

In addition, people with higher autistic traits may benefit more from OT in terms of empathic accuracy. In autistic people, OT seems to increase amygdala reactivity which contributes to improvements in social salience and behavioral performance. Therefore, it is essential to consider individual-related variables when examining the effects of intranasal OT on socio-cognitive processing and the processing of socially-salient stimuli.

Oxytocin’s Context and Person-Dependent Nature

As we’ve discussed thus far, many studies have investigated the pro-social effects of oxytocin in humans, which are behaviors that facilitate interpersonal relations (e.g., trust, generosity, cooperation, attractiveness, approachability, etc.) However, oxytocin’s nature is highly variable, and with it, its effects. Human oxytocin literature has shown that the effects of exogenous oxytocin on social cognition and prosociality are more nuanced than we previously thought. In fact, studies have shown that the positive effects of oxytocin on trust-related behaviors disappear if the potentially trusted other is portrayed as untrustworthy, is unknown , or is a member of a social out group (and out-group threat is high), in these scenarios, oxytocin may even decrease cooperation. Therefore, beyond thinking of oxytocin and its effects on trust and prosociality as constant and uniform, we should consider its dependency on situational factors that affect the salience of trust-related or trust-inconsistent cognitions (i.e., cooperation vs. competition, trustworthiness vs. familiarity, and individual differences vs. interpersonal uncertainty).

We must approach oxytocin’s potential as a societal-enhancing drug with equal parts curiosity and caution. Empirical support for oxytocin exerting situation-invariant effects on behavior (i.e., improving social cognition and promoting prosocial behavior) is mostly inconsistent. In most cases, the effects of oxytocin are moderated by contextual factors, like the features of the situation in which oxytocin is administered or by constant characteristics of the individuals to whom oxytocin is administered. These inconsistencies serve as clues to the context and person-dependent nature of the effects of oxytocin. By characterizing this context and person-dependency we broaden the theoretical perspective on the social effects of oxytocin in humans. In fact, this approach views oxytocin as an individualized therapeutic agent, using an intersectional lens to examine how multiple factors interact to produce specific positive (or negative) effects.

Implications for society

Oxytocin’s mechanisms and effects are far from simple, yet within its complexity exists immense potential. Even then, what do oxytocin’s positive effects mean for society? Well, until now, we’ve learned about how oxytocin induces an approach-oriented profile, increases prosociality and even trust among people. Similarly, oxytocin plays a pivotal role in the context of compassion, it is often linked to various indexes of care and empathy. Compassion is a warm response of care and willingness to alleviate suffering, and understanding its mechanism is relevant, as compassion cultivation is widely linked to multiple beneficial effects for individuals and society as a whole.

Besides playing a key role in increasing positive feelings like generosity and prosociality, allowing people to readily engage in social contexts, oxytocin also plays a biological role in relation to social stress. Oxytocin has been found to affect physiological activation, enhancing biological readiness to approach and engage in social contexts, this is what we’ve come to know as the approach-oriented profile. Oxytocin is related to cardiovascular and behavioral indicators, which supports its association to a positive or “challenged” state under conditions of social stress. In a study where oxytocin was administered to participants following a stressful task, it was shown to induce a healthier recovery profile (as indexed by greater vagal rebound). In addition, OT has been identified as a central cardiovascular modulatory peptide, indicating key cellular mechanisms in which it modulates sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in response to social stress. By examining oxytocin’s complex nature, we can better understand the important role it plays in modulating social stress responses, and potentially use it in our favor.

The Social Saliency Hypothesis

As mentioned above, oxytocin’s effects and influences on social behavior are complex, and aren’t as simple as just increasing compassion or generosity. Previous research has shown that the administration of intranasal oxytocin enhances attention to social stimuli and affects the saliency of critical features of these stimuli. This literature suggests that oxytocin plays a central role in saliency signaling (i.e., noticing social cues), which may or may not lead to pro-sociality. Even though oxytocin increases attention to social cues, the positive or negative effects that come from it will depend on multiple internal and external factors. To better navigate these diverse findings, researchers proposed the Social Saliency Hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that rather than inducing pro-social effects, OT regulates the salience of social cues by modulating attentional shifts. Therefore, in an oxytocin-enriched environment, social cues have a higher potential to be noticed, identified, and responded to. What can we learn from the Social Saliency Hypothesis? Well, maybe that we should prioritize fostering oxytocin rich environments so its positive outcomes may take full effect. A critical example of this is the mother and baby breastfeeding context, an ideal setting where trust, social bonding and attachment are promoted. Identifying other factors and scenarios that drive interactions towards positivity would allow us to better understand oxytocin’s prosocial effects beyond the social contexts of a mother and her baby.

Research further suggests that oxytocin may mediate individual differences in compassionate behaviors by interacting with personality and contextual factors at different processing stages. Therefore, the outcomes of oxytocin could possibly be divided between processing stages and external and internal factors. Because individual differences may affect the degree of oxytocin released in response to social cues, the saliency of social cues is either increased or decreased. Considering how these individual differences impact the way OT manifests itself in people is helpful and demonstrates its nuanced nature. For example, individuals with a high sense of social power have a lower propensity to care for others in distress, even though they detect the need for help. In contrast, highly empathetic individuals are prone to physiological contagion than those with lower dispositional empathy. This shows that oxytocin’s context and person-dependent nature matters, and it should change the way we look at the effects it produces. Whether it’s enhancing compassion and pro-sociality or increasing trust and generosity, OT contributes to positive effects, and it may be used in beneficial ways. The key is to better understand the complexity of its mechanisms that lead to said positive outcomes. Considering its nuanced and variable nature is crucial as we move forward in learning about the way it impacts individuals and in a bigger scale, society.

So where does this leave us?

Oxytocin is clearly a powerful hormone and one that can be and is the target of much research to develop effective therapies for treating specific syndromes (e.g. autism) and promoting social behavior in groups where it is needed (e.g. AL’s undergraduate research as discussed in the opening). It also comes with risks (e.g. enhanced out-group conflict) that might be mediated with proper context setting or even cognitive behavioral therapy methods. Perhaps, its greatest contribution is to reveal brain mechanisms of approach-oriented profile that we could promote through behavioral systems to groups and individuals in need. In that way, the brain’s OT could lead us in better understanding of ourselves and our social interactions in a broader way than its useful specific applications. So much of what we do is with and for other people, and learning more about how and why we act in social contexts could be a gateway for building deeper connections with those around us. As we continue exploring oxytocin and its potential, the positivity, generosity and trust we show will exemplify what we ultimately aim to achieve with it.

One Response to “If Oxytocin induces an approach-oriented profile, what does that mean for society?”

Kenira Thompson says:

I truly enjoyed reading this! Extremely interesting insights into the role of OT on social interactions. I look forward to future posts on the “otherlobe”!