What are Emotional Layers and how does it relate to the Hedonic Continuum?

By Dana Morales-De Brecourt UA 25 and Jim Stellar

In our previous blog, we explored prefrontal cortical function and the concept of the hedonic continuum. There we looked at how it helps us to understand the interactions between two opposing emotional and motivational states (e.g., hungry-satiated) that are represented in limbic and cortical brain structures. As often happens, we were left with many unanswered questions. One of which is how the brain structures, classically associated with approach and withdrawal, even going back to JS’ doctoral thesis, relate to one another. And what happens if the experience leads to simultaneous mixed emotions, such as going to get something you want but fear is involved (e.g., asking someone you like for a first date while also fearing rejection)?

One additional idea here is that our mood differs from our emotions and feelings behaviorally because they are less specific, less intense, and less likely to be provoked or instantiated by a particular stimulus or event. However, our emotions, on the other hand, we look at here as more intense and situational, fluctuating more dramatically along the approach-withdrawal hedonic continuum. Our thinking is that we feel our emotions more immediately, and they have clear triggers, such as when we experience happiness or joy upon receiving good news or when we feel fear or dread in response to danger. But the idea of experiencing these mixed or in-between emotions does not seem to fit into the same hedonic continuum framework. How could we hold two emotions at once if the systems which mediate them are opposite in valence and perhaps neurally inhibit one another? Would this mean we are flipping back and forth between the two states, or perhaps we are creating a new third state?

How are complex, or in between (mixed), emotions formed in the brain?

It is a very difficult phenomenon to explain, and many researchers, like Lisa Barrett, have investigated and written about the idea of the brain processing mixed emotions and, indeed, creating them. She challenges our traditional views of fixed circuits underlying specific emotions and suggests that emotions, particularly mixed emotions, are not as simple as we may think. Anything but the simplest and most basic emotions (e.g., this sucks, or this is great), we would argue, comes from limbic brain areas and also features cortical-limbic connections which allow integration with cortical cognition.

Therefore, we would say that our experiences, whether from an internship in college with both good and bad properties, are complex, just like our emotions. When we experience these mixed emotions, our brain makes predictions based on past experiences, which sometimes correspond to multiple categories, almost like we combine elements from different emotional experiences or generate unique emotional concepts. For example, you may love someone deeply and still experience the fear of losing them. This might lead to a combined complex emotional experience like anxiety. This is known as “conceptual combination” and is particularly discussed in Barrett’s book How Emotions Are Made. So, our emotions are not inherently fixed as positive or negative on a hedonic scale; instead, they are contextual and dependent on how our brain interprets an event.

How Emotions are Made book by Lisa Barrett – What about the inbetween?

If emotions are constructed and fluid (as Barrett says in her book) and are not hardwired, this makes the reflection on the experience of mixed emotions even more complicated when relating it to brain structure. Drawing on multiple emotional concepts that overlap makes it challenging to make anatomical sense of complex situations, and this presents an interesting behavioral challenge to understand them neurally. Barrett (again above) argues that cultural and social differences influence the way we label these emotions. Her research indicates a consistency in how people categorize emotions, which may not stem from an innate understanding of emotions but rather from societal expectations that encourage us to simplify and classify our emotions into distinct categories.

In addition to our experience and environment, our emotions are also closely tied to our language. We all may differ in how we label and interpret our emotions, and the way we do so influences how we define our experiences and categorize them. Imagine feeling butterflies in your stomach right before that in-class presentation you’ve been anticipating; one person may label this as excitement, while another person may call this feeling anxiety. Sometimes, it can be challenging to find a single word that accurately describes how we feel, leading us to use multiple emotional labels, especially in moments of mixed emotions.

How do you differentiate in a moment of mixed emotions?

In a moment of mixed emotions, we argue that our brain may use anchoring, an effect often attributed to Kahneman’s research, which may be based on our initial response to sensory information and using learned associations to make predictions about how to interpret and respond to sensory information. Once this anchor is set, it adjusts our other emotional elements. For example, consider the brain anchoring sadness from a past negative experience; it’s likely your brain will anchor this emotion in similar events with similar features even if the situation isn’t actually negative. The same goes for happiness with positive experiences.

People likely experience mixed emotions in different ways. Sometimes, these emotions are bittersweet, like when someone feels proud to graduate but also anxious about what the future holds. At other times, emotions conflict with each other, such as the excitement of riding a roller coaster, which still leaves you with the fear responses of a racing heart and sweaty palms. We can also face more complex emotional situations, such as looking at old photographs that evoke both happiness and sadness, as those moments are now gone.

In some cases, these conflicting emotions happen all at once. For example, someone in an unhealthy relationship might feel emotional confusion. They are juggling multiple processes, managing emotions, making decisions, and dealing with attachment and reward, all at the same time. This overlap can make their emotions feel inconsistent, leading them to experience rapid emotional shifts and a truly complex emotional experience.

It seems our brains are switching between mixed emotions or perhaps changing what we may categorize our emotional experiences to be. It becomes challenging to categorize mixed emotions, especially when we feel two opposing emotions on opposite ends of the hedonic spectrum or experience two mixed emotions at the same time. To categorize these emotions, we can think of these in two categories. When we experience multiple emotions simultaneously, such as the feelings I (DM) had after presenting for JS in our senior seminar Sp’25 class, where I felt both proud and nervous at the same time. These are examples of simultaneous mixed emotions. At other times, we might experience a range of emotions one after the other, such as receiving a job offer and feeling excited and happy about a new opportunity, but over time, you may start to feel anxious and overwhelmed about what lies ahead; these are sequential mixed emotions.

How are these mixed emotions related to other phenomena?

Dissociative Identity Disorder: When our brain processes these mixed emotions and faces emotional conflict, it can happen outside of our awareness. When we struggle to make sense of our mixed emotions, sometimes it leads to emotional dysregulation, identity confusion, and, for others, dissociation. Consider, for example, Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), which is characterized by multiple personality states and is believed to be caused by several factors, from stressful to traumatic experiences usually occurring during early childhood. When someone experiences repeated trauma, it’s hard for their brain to process mixed emotions simultaneously. Instead of creating a more integrated complex feeling, the DID brain compartmentalizes them into different identity states- switching between alters (sequential manner) or an altar in consciousness (simultaneously). Over time, these states become distinct and lead to dissociated identities, and so the brain avoids overwhelming conflict.

Borderline Personality Disorder: Another condition is Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) on the other hand which is linked to intense, rapidly shifting emotions, fear of abandonment, and difficulty in emotion regulation. These individuals often experience black-and-white thinking, being fond of someone and hating them the next, rather than integrating mixed emotions. Their brain flips between extremes.

In both disorders, we see this disconnect, and in any of us, it becomes tough to truly understand how to categorize these mixed emotions if they don’t make sense and if we do not know how they are processed. For example, do our mixed emotions arise from combining features of different emotions or from distinct emotional cascades unfolding over time? How are we able to differentiate in a moment of mixed emotions if some occur outside of our conscious awareness?

Emotions outside conscious awareness – The famous case of Anna O. by Freud

The Anna O. case, is about the story of Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of Josef Breuer, who presented with a range of physical and psychological symptoms, from paralysis, hallucinations, speech disturbances, dissociative symptoms, and emotional disruptions. Despite being diagnosed later with hysteria, Freud explains that her symptoms were caused by emotional disturbances and a sense of disconnection. Anna’s case revealed some ideas about the impact of emotional experiences. Her symptoms stemmed from the emotional strain of caring for her sick father; as a result, she struggled with unresolved emotions, leading to a disconnect between her mind and body. During episodes of absence, Anna would mutter words that reflected her inner thoughts, indicating that her emotional struggles were always present, even if she couldn’t fully express them. However, when she was able to bring these suppressed memories to the surface through hypnosis, she found it easier to confront and express her emotions, which ultimately helped to provide some relief of her symptoms.

Anna’s case demonstrates that her mixed emotions, love for her father but fear for his health, and internal feelings of disgust and helplessness were intertwined and often operated outside her conscious awareness, contributing to her symptoms. It became very difficult for her to differentiate in a moment of mixed emotions outside of her awareness. Still, during her treatment, through self-reflection and expression, she was able to navigate her mixed emotions.

The Default Mode Network (DMN)

This is likely where our default mode network comes into play in this case and in mixed emotions. It supports our internal narrative of the self. Recent Neuroimaging studies have shown that the DMN underlies our self-referential cognition (self-directed thought, self-reflection, emotion processing), remembering our past, environment, our future, and reflecting on our emotions. The DMN plays an even more important role as the brain’s integrator of complex emotional information. In moments of mixed emotions, the DMN allows us to integrate conflicting emotional signals into one subjective experience. That is in emotionally healthy individuals. But when a network active during rest (i.e., daydreaming) is disrupted, how would this network turn on? Well, things may start to happen unconsciously, such as Anna O’s symptoms of depersonalization, dissociation, and trouble with memory retrieval. These symptoms arose when Anna’s integration of self-related information was impaired due to her trauma. But, they weren’t just mental; they manifested physically too, almost as though her DMN was unable to coordinate with her task-positive networks (salience or executive). In her case, her DMN imbalanced her core brain networks with unresolved emotions and memories. Her salience network (SN) struggled to filter or focus her attention, while her executive network didn’t allow her to exercise control over her symptoms.

Interestingly, Anna was able to reintegrate her fragmented self-experiences – perhaps her “talking cure” was helping to restore her normal DMN functioning by re-establishing a coherent narrative identity.

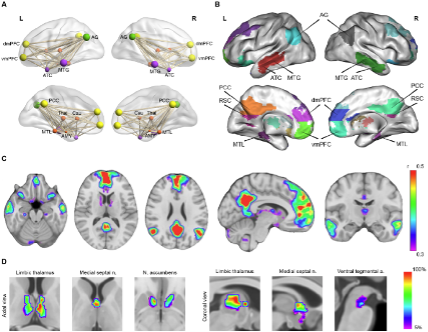

But what Anna’s case ignited was an even bigger idea. If DMN dysfunction may be linked to a disruption in self-functioning, a hallmark of many personality disorders, perhaps there is some connection here. Neuroimaging studies have even associated dysfunction in the DMN (see the figure below) with dissociative disorders. Patients with these disorders often exhibit abnormal connectivity within the DMN and show altered engagement when at rest.

The Human Default Mode Network

Above, we see highlighted the key cortical regions (medial PFC, PCC, angular gyrus) and subcortical nodes of the DMN. To form our ongoing internal narratives, the DMN integrates these regional processes (e.g., memory, emotion, language, and semantic representations), which are reflective of what Barrett calls our individual experiences as in Menon’s 2024 paper. When people rest quietly, with their eyes closed, these DMN nodes become synchronized, which may reflect our internally directed cognition (IDC).

This network is also closely related to our emotion regulation and bodily state monitoring, working with the SN, allowing us to conceptualize our emotional experiences, “abstracting sensory inputs into meaningful emotional categories.” Neuroimaging studies have suggested that the DMN plays a role in constructing discrete emotions (such as anger and fear) by providing context for our emotional signals. In moments of mixed emotions, what might this indicate is if the SN acts like a traffic cop, shifting between our inner thoughts (DMN) and task-oriented focus from the central executive network (CES) and may have this led to an overdominance of Annas’s DMN, which resulted in her inability to coordinate a unified self-narrative and essentially her symptoms.

A new model

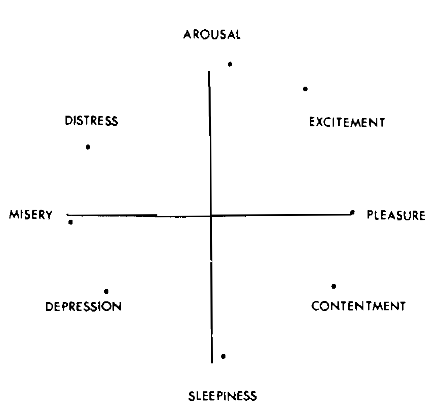

Imagine if we could create a hedonic scale that truly reflects the intricacies of our emotional experiences, a tool that accurately captures the way we experience feelings in all their complexity and temporal dimensions. Instead of the traditional hedonic scales, which utilize good and bad emotions, we could develop a multi-layered scale that captures the fluidity of our feelings and allows contradictory, mixed emotions to coexist rather than being mutually exclusive. Consider Russell’s old (1980) Circumplex Model of Affect, which consists of two dimensions of arousal and valence, as shown in the figure below.

Russell’s circumplex model of affect (from his figure 1)

Russell’s circumplex model of affect, resembling a compass (above), maps emotions along two dimensions. The horizontal dimension (east-west) valence ranges from pleasure to displeasure, and the vertical dimension (north-south) arousal ranges from arousal to sleep. Emotions are then placed in this circular space based on their levels of valence and arousal. So, if you’re feeling anxious, you would have a high arousal and negative valence versus feeling relaxed with a low arousal and positive valence. But in more complex emotional experiences, such as when we experience mixed emotions or in individuals with BPD or DID, as discussed later, this accounts for the lack of balance the brain exhibits between its core networks (DMN, SN CEN, as mentioned above).

How do mixed emotions relate to DID and the Russell model?

When emotions in personality disorders such as DID arise, it is perhaps because these individuals experience emotions through separate identities or alter during moments of unawareness. Sometimes, these alters feel contradictory emotions about the same situation. Such as, if one alternate personality is feeling panicked due to PTSD, they’d fall into the high arousal and low valence area (near fear or anxiety). As opposed to another alter that might feel calm about the same situation, and that alternate personality would be towards more low arousal and low valence (e.g. near depression). This model of emotion helps expand the emotional hedonic continuum notions that started this blog by allowing us to categorize the above emotions based on two dimensions instead of one. This model may have been helpful in understanding the complexity of Anna’s emotions – which she experienced during her treatment, and may explain Anna’s ability to transition from a state of high arousal and negative valence (anxiety and distress) to a state of lower arousal and more positive valence (relief or calmness).

Does mixed emotion lead to dissociation, not DID?

Well, this is what the case of Anna O. suggests since she was never fully aware that her feelings were associated with her symptoms. However, through treatment (hypnosis + verbalizing feelings), she was able to understand the causes of her symptoms, reference her internal thoughts, and engage in her DMN’s functions (self-reflecting, processing her memories). Perhaps creating a balance. As college students, we mildly dissociate quite often; whenever we zone out or mind wander. This activates our DMN. It may not be to Anna’s extent, but it can occur in class when emotionally intense subjects are discussed, and we feel detached. We focus on our internal thoughts and take our attention away from the external environment.

During moments of mixed emotions, what if our DMN is activated? A network known as the brain’s integrator of complex emotional information must play a crucial role in processing complex emotional states, allowing us to integrate opposing feelings to construct our mixed emotions. An example might be my feelings towards my graduation ceremony. I (DM) feel very proud and happy about my achievement, but I’m sad about parting ways with my mentor, JS. My DMN allows me to reflect on these emotions, considering my current feelings, past memories, and the future. But, when I become focused on externally focused tasks, such as adjusting to new environments, such as moving from a public undergrad like UAlbany to a private grad school like NYU, my internalized self-concept might be challenged and perhaps suppress my DMN. In fact, JS and I are curious about what imbalance this might bring to my core brain networks, perhaps the topic of our next blog.