Broken heart syndrome – an example of cognitive-emotional integration and vagus nerve function

Catherine Lienemann ‘UA 26 and James Stellar

I’ve (CL) occasionally felt pain in my chest, an aching, stinging feeling that eventually fades. Usually it comes when I’m stressed, or suffering from intense emotions like grief or anger – my self diagnosed broken heart syndrome.

The actual broken heart syndrome is what is also known as Takotsubo syndrome, which is described in a recent paper. They say that Takotsubo syndrome is a form of stress-intensified cardiomyopathy that results in the physical dysfunction of the left ventricle that comes from the muscles of the ventricle becoming atypically thickened in some spots and thinned in others. The name comes from its resemblance to a pot or a traditional octopus trap which is called a ‘takotsubo.’

Now there are a couple theories of the causes of the syndrome, but nothing scientists have “set their heart on” (pun intended). Correlation between menopausal and Takotsubu syndrome may indicate that reduced estrogen is a root factor. A few researchers indicate there could be a genetic factor. But one of the most promising origins of the syndrome is focus on psychogenic factors such as anxiety and depression that have heightened stress responses that impact the heart. This ties back into the triggers of major emotions and the stress related response. It also ties to the general theme of this blog series on cognitive-emotional integration, but more focused on physiology than on the typical topic of how college students learn from their “heart-felt” experiences from internships to better inform their cognitive plans for their major field of study and their career after graduation.

Our first question simply is whether the brain is to blame for this condition. The answer is yes, and no. There’s not any kind of abnormality within the brain that is known to produce this syndrome, but outside events such as triggers and trauma can cause the sympathetic/neurohormonal axis to elicit this syndrome. For example, a survey study in 2021 found that patients diagnosed with broken heart syndrome often experienced a stressful event within the day of their cardiac event, and importantly, perceived it to be more negative than patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Of course, Takotsubo syndrome doesn’t just appear out of the blue like a stroke would, nor is it the consequence of a poor diet and lack of exercise. It is a trauma-related health effect. It is also interesting that in this paper cited above that more than 94% of patients with Takotsubo were female – a statistically significant finding even with a sample of only 54 patients. It is almost as if women undergo an increased stress reaction compared to males. Maybe the female brain processes stress and anxiety differently. Later, we will discuss how it involves the vagus nerve and how that affects the brain.

One might think that there is no sexual dimorphism in the processing of stress, but estrogen itself is known to play a role in stress reactivity of the stress response. A paper discusses this difference of the sexes, and initially, men would have a greater autonomic response when compared with women when tasked with something like public speaking. However, in normal conditions, women have higher levels of stress hormones. This could be attributed to estrogen causing a delayed response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, allowing the stressor to affect the body for a longer period of time. In relation to Takotsubo syndrome, the prolonged stress response could be the reason that women seem to be more affected by this syndrome, as quicker responses leave less damage while continual stress leads to greater stress on the heart and the parasympathetic nervous system. The above paper also discusses the reflection of emotions after stress related tasks that acts partially as a continuation of that stress. This is a process very common in women when dealing with stressful situations.

Now, this higher prevalence of Broken Heart Syndrome isn’t just in women–specifically it is in menopausal women. Menopause is itself a notoriously stressful event in life where one’s body undergoes a major hormonal change. This study researchers examined stress and regulatory patterns of women going through menopause. Pre-menopause, women have a natural coupling of menses, stress and fatigue and for a long time have a regulatory function for women. But during menopause that regulatory function pattern is thrown out the window and they have to learn to develop a new process of handling stress. We could stop this investigation right here, but there has to be another interesting neurological cause.

There is the old saying “My heart is not in it” that applies to how people sort out what they want to do in life. We think that broken heart syndrome is related to the milder form of cognitive-emotional integration that this blog series is all about where we explore how learning from an experience like an internship impacts a college student’s major field of study. This thinking starts with the idea that cognition itself is integrated with the body and perhaps particularly the heart.

The Vagus Nerve

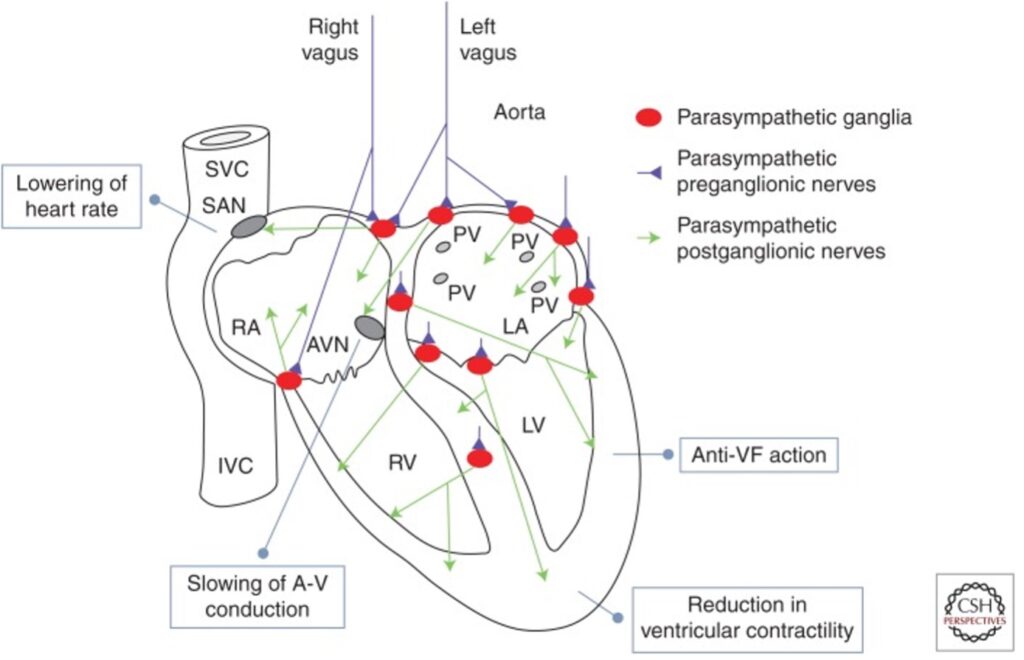

A big part of the story here is the vagus nerve which innervates the heart (as shown above) and is a major part of the parasympathetic component (i.e. slowing, rest) of the autonomic nervous system. What impresses us here is that much of the vagus nerve innervation (more than 60%) of the vagus nerve is actually bringing sensory signals back to the brain from the heart and other organs. This input relates to research where much of this innervation is becoming clearer and the focus is on the impacts on the brain and behavior. Here a large effect is seen with stress and the impact of vagus input on key brain areas according to a recent paper on the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala brain regions.

In a comprehensive review of the internal sensory functions of the vagus nerve (and more briefly in the figure shown below), the vagus nerve is seen as being responsible for reporting a majority of the internal processes occurring in your body. Connected from the brain to your gut, it has organs like the heart, lungs, throat, liver, intestine, stomach, pancreas, and aortic arch on its roster. It’s also responsible for calming the heart after a fight or flight moment, creating the appropriate changes to go back to normal.

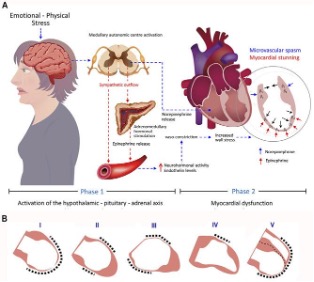

To go back to broken heart syndrome, the citation to the above figure points out that it occurs in two phases. One phase which is started by a stressful event which then activates the medullary automatic center. Which then stimulates the release of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and other neurohormones, of which in the absence of higher estrogen levels that would ordinarily prevent that stress from acting in such a way on the heart. In combination, in phase 2 it creates a spasm of one section of the atrium and a stunning (transient post-ischemic myocardial dysfunction) of the other.

We will come back in a later blog to this topic of the effect of the vagus nerve on the brain, but for here we want to say if the vagus nerve can play a role in Broken Heart Syndrome, imagine what it can do to brain function more generally. Now, remember that finding your way through college into a career is stressful for many college students and how living and working with that stress can lead to brain-stress alterations as one moves through college to a career, particularly in pre-medical field – perhaps one of the most stressful college tracks.