What the vagus nerve and the hormone oxytocin tell the frontal lobe to do about stress

Catherine Lienemann ‘UA 27, Alondra De Lahongrais Lamboy AGMU’26, and James Stellar

We three came together in the spring of 2025 to produce a poster for the University at Albany research day on 4/30/25 called the “Showcase.” We did that after Catherine posted two blogs on the heart and the vagus nerve, and after Alondra posted one blog on oxytocin. These two subjects led us to the topic of higher-level cognitive brain function, such as frontal lobe planning that connects with emotional input from the limbic system. This seems even more important when we consider the emotional topic of stress in college students, which seems to be at a high level today, and its management by students. So, what are some of the relevant brain mechanisms that influence stress and the way we approach it?

The Vagus Nerve: The vagus nerve, also referred to as the wandering nerve, plays a crucial role in monitoring the parasympathetic nervous system. Just recapping, the parasympathetic nervous system is mainly active during times of low stress, when the body believes it can “rest and digest.” But during times of stress, our body switches to the sympathetic nervous system for “fight or flight.” The vagus nerve also monitors the body’s functions in the heart, lungs, and gut, in addition to slowing heart rate, stimulating digestion, and regulating breathing – all things that are necessary to help us function and maintain basic homeostasis. Our focus here is on what the vagus nerve tells the brain about the state of the body, particularly since, as we discussed, some 80% of the fibers in the vagus nerve are sensory, reporting to the brain.

Oxytocin: Oxytocin (OXT) is often referred to as the “cuddle drug” or “love hormone”; it even has a song on YouTube that characterizes it as the potion of devotion. Even though finding someone attractive, cuddling, and hugging does produce oxytocin, this hormone and neurotransmitter is complex, and its actions go beyond these effects. In our last blog, we presented oxytocin as a hormone that induces an approach-oriented profile, which means that it increases our desire to engage in social interactions. Oxytocin has been found to facilitate sensory processing to preferentially receive socially salient signals, facilitating reward values of prosocial behavior. So, in many ways, oxytocin prepares us better for these social interactions, allowing us to spot and respond to positive social stimuli, making us engage in more positive interactions. It also reduces anxiety (and even induces satiety), resulting in appropriate active coping behaviors being taken to adapt to the social environment.

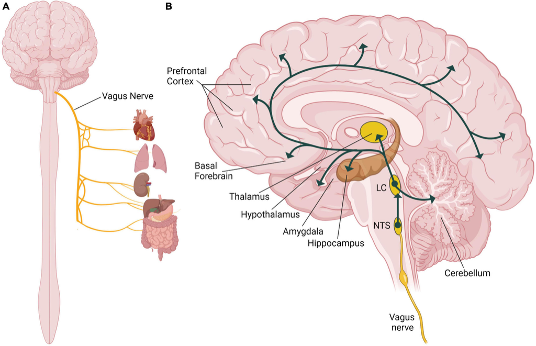

Vagus nerve connections in the brain: The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve and, like the others, it emerges directly from the brain. But unlike the rest of them, the vagus nerve extends far past the head and neck, down through the heart, to the lungs, and down into the gut. Given that, as stated, 80% of the nerve consists of afferent or sensory input fibers, it provides important feedback to the brain about the state of the body. More specifically, the vagus pathway (figure below) first reports from the body’s organs to the superior vagal (jugular) ganglion and the inferior vagal (nodose) ganglion, ending in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem. Also shown in the figure below, the NTS then sends this information to various parts of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and the parabrachial nucleus. It is thought that these afferent projections are responsible for the behavioral effects of vagal nerve stimulation (VHS) in its antidepressant effects and its anticonvulsive effects, in addition to altering what we might call the subconscious feelings from embodied cognition.

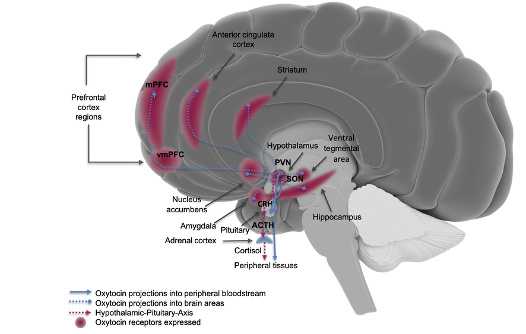

Oxytocin connections in the brain: Oxytocin is synthesized in the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei and projected to the pituitary gland, where it is released into the peripheral bloodstream. Oxytocin is also released from hypothalamic neurons, specifically from PVN axon terminals, that directly project into cerebral mid and frontal regions like the prefrontal cortex, as shown in the figure below. It also shows up in the striatum (a classical motor area that has to do with action), and amygdala (already mentioned in association with emotion, particularly fear), where it binds to oxytocin receptors. In addition to traditional release across a synapse at the end of the neuron’s axon, oxytocin is also released from neuron’s somas and dendrites and can reach nearby brain regions via volume transmission, i.e., by diffusing across neural tissue. This neurohormone interacts with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system, and appears to buffer the stress response. Also, with dopamine release from the mesolimbic reward system, oxytocin directs motivational behavior to approach and engage in social activities. This is what we already argued creates an approach-oriented profile, which essentially results in becoming more aware and open to social interactions. This effect can be especially important, since social relationships are highly associated with the activity of the oxytocin system. For instance, studies have found that intranasal oxytocin administration can reduce the cortisol response during couple conflict, promoting positive communication, and it may play a role in reducing stress, but this effect is variable.

Our focus on the prefrontal frontal cortex: One of the chief premises of this blog series is that the neocortex is the basis of cognitive function that has given us humans language, abstract thinking, social interactions, culture, and our ascendancy as a species with control over our lives and even our planet. Much of that planning depends upon the activities of the prefrontal cortex. We have recently argued that this abstract logical ability (vs. a simpler form of processing at a reflex or limbic system level) comes from the unique columnar structure of the entire neocortex. Further, we argue that the prefrontal cortex is somehow integrated with the limbic system function to try to extract value propositions or situations (Is this good for me?). We note that the evolutionary older limbic system operates without a columnar structure, and perhaps it operates somewhat in parallel with the neocortex. We think this cognitive-emotional integration is important to how college students grow, manage stress, and learn from direct experiences in the field about their academic plan of study.

Vagus Nerve inputs to the frontal cortex: In a 2021 study, researchers investigated how vagus nerve stimulation affects frontal cortical activity (prefrontal cortex specifically). Researchers used macaque monkeys in which they stimulated the left cervical vagus nerve while recording local field potentials of the cortical areas. That study found that this stimulation produced vagal-evoked potentials in the prefrontal cortex, and higher VNS frequencies led to stronger cortical responses. For non-neuroscience enthusiasts, a cortical response is the brain’s measurable reaction, like an electrical signal to a stimulus—essentially what excites its neurons to fire. It’s one of the ways researchers can identify what processes occur in the brain and what regions of the brain are responsible for them. We can identify that before the prefrontal cortex activity increases with vagus nerve stimulation, some of the afferent fibers report to that, which we could attribute to certain calming effects of vagus nerve stimulation.

Oxytocin inputs to the frontal cortex: In rats, bilateral direct oxytocin administration into the prelimbic part of the medial prefrontal cortex has been shown to have anxiolytic actions, reducing anxiety?related behavior and facilitating social interaction toward unfamiliar conspecifics. In humans, intranasal oxytocin administration has been shown to increase activity and functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex with large scale brain networks, also other areas such as the posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus, decreasing amygdala activity and facilitating extinction of fear conditioning. Oxytocin has also been found to act on the prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuit by controlling fear or threat responses to attenuate behavioral avoidance or autonomic stress responses in return to negatively valenced stimuli.

Applications to Therapy

Vagus Nerve Stimulation from Massage Therapy: A 2020 study examined whether massages can induce psychophysiological relaxation. In this study, they had 3 test groups. One where the vagus nerve in the neck was deeply stimulated, one group that had a small soft shoulder massage, and a resting control group. They measured heart rate and heart rate variability (HF-HRV) in the participants, which is a marker of vagus nerve activity and the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. What they found is that high frequency heart rate variability markers were significantly improved (and subjective stress was decreased) in the massage intervention groups in comparison to the control group. Possibly indicating that the massages, specifically around the neck where the vagus nerve is more exposed to pressure stimulation, can induce relaxation.

Oxytocin Increase from Massage Therapy: In a 2012 study, other researchers examined the effects of massage on oxytocin and other physiologic factors, including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), nitric oxide (NO), and beta-endorphin (BE). They found the massage to be associated with an increase in oxytocin and reductions in ACTH, NO, and BE. The team showed that 15 minutes of skin-to-skin, moderate pressure back massage resulted in a 17% increase in oxytocin within subjects. As the authors pointed out, massage may promote prosocial behaviors such as trustworthiness and empathy, which could be directly linked to the increase of oxytocin they observed.

Another study investigated whether hand or machine-administered foot massage is effective in promoting endogenous oxytocin release and activating both cognitive and reward components of the neural system responding to social affective touch. Researchers found that the hand-administered foot massage evoked a large increase in plasma oxytocin (51.8%), in comparison to the machine-administered massage, which evoked smaller increases in oxytocin (18.2%). This supports what we know about physical touch and oxytocin, and implies that physical touch is important to activate the full positive effects associated with oxytocin.

Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for depression: Direct electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve in the neck through a pacemaker-type device is now an approved treatment for depression. It works by stimulating the vagus nerve with electrical pulses through the more accessible nerve point in the neck, which then carries this stimulation targeting the “locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus.” Instead of treating the symptoms of a chemical imbalance, VNS is a “bottom-up” approach in which it targets deep brain structures instead of altering the synapse transmitters like with medications. The process of electrically stimulating certain pathways in the brain has been coined “neuromodulation,” and unlike Electroconvulsive or ‘shock’ therapy, it’s less stigmatized and hasn’t been found to impair memory function. Actually, shock therapy was found to be very effective in treating treatment-resistant depression, but has been unutilized due to the stigma it carries, often being regarded as barbaric. In TV and movies, ECT is almost always represented in a horrific way, such as in movies like: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), The Snake Pit (1948), Frances (1982), Shine (1996), Shock Corridor (1963), the Cult of Chucky (2017) and others you can find online.

Oxytocin as a treatment for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD): Here, oxytocin is regarded as a potential therapeutic agent, despite some clinical research skepticism about its effectiveness. As oxytocin is known for enhancing social behavior and reducing social fear, the idea is that administering it to patients with social deficits, whether caused by social anxiety disorder (SAD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), could help enhance social performance. This idea is supported by reviews that suggest oxytocin can also enhance the salience of negative interaction, and even modulate non-social cognition and behavior. In a 2021 study, researchers found that a single dose of intranasal oxytocin could enhance SAD patients’ social performance. Interestingly, oxytocin did not affect the patients’ anxious appearance, but it did improve their social behavior. So even if patients remained “anxious-looking”, oxytocin administration still allowed them to engage with others with more ease. However, oxytocin is very context-dependent; in a negative social setting, it could promote avoidance behavior, while in positive social settings, it can enhance approach-oriented behavior. Ultimately, oxytocin administration has the potential to improve social behavior, which could reduce the negative influence that feeds social anxiety in SAD. Among the prospective uses of oxytocin, its possible treatment of social deficits solidifies its role as a therapeutic agent of importance.

Relation to Stress

The vagus nerve and oxytocin both provide essential input to the frontal cortex, which plays a key role in how we manage and regulate stress. One important area, the medial prefrontal cortex, helps regulate the amygdala, an emotional center in the limbic system responsible for generating fear and anxiety responses. Stress is a state of threatened homeostasis in response to experiences that cause physical, emotional and psychological challenges that exceed the capacity of the individual to cope. When the vagus nerve sends afferent signals from the body indicating a calm or resting state, it activates the prefrontal cortex. This activation supports a shift toward parasympathetic activity, promoting relaxation and reducing the stress response.

The regulation of stress responses by oxytocin is observed in different social situations, an essential component of our lives as social creatures. Oxytocin regulates stress responses that show up in our behavior, and in the neuroendocrine system, autonomic nervous system, and immune system. Research has found oxytocin to reduce the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, regulate autonomic stress responses, and reduce anxiety-related behaviors. Studies with human subjects have proved the anxiolytic effects of intranasally administered OXT along with social support, decreasing cortisol levels and reducing anxiety. In fact, in humans, social buffering is associated with a single nucleotide polymorphism of the OXT receptor gene. We know to be true that the OXT system is activated in response to stress, also in socially affiliative conditions, and that it plays an essential role in attenuating our body’s stress response. The OXT system also mitigates stress responses by prompting the search for social support and obtaining it.

Interactions of the vagus nerve and oxytocin

Together, the Vagus nerve and oxytocin’s input enable the prefrontal cortex to modulate stress by dampening overactive emotional responses, like PTSD and anxiety disorders, facilitating a behavioral profile characterized by openness, social engagement, and calm problem-solving. For example, high vagal tone has been associated with improved emotion regulation and social connection, while oxytocin has been found to reduce social fear and promote prosocial behavior. These effects are particularly relevant for college students, where academic and social pressures can lead to chronic stress. When the vagus nerve and oxytocin systems are functioning optimally, they appear to support a prefrontal-centered regulation of the stress response that results in more adaptive coping strategies, reduced anxiety, and greater readiness for social and academic engagement.

During our research for this blog, we found studies linking the effectiveness of oxytocin to the integrity of the vagus nerve. Recent research shows that oxytocin needs the vagus nerve to have its full effect on the brain, especially when it’s given through the body (like an injection or nasal spray). In a study with rats, scientists found that oxytocin reduced methamphetamine (METH) use and relapse, but when the vagus nerve was cut, these effects mostly disappeared. This means the vagus nerve is a key pathway for oxytocin to be able to send calming and behavior-regulating signals to the brain.

Another study explored the effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) by dividing participants into two groups—one received the stimulation, while the other received a fake (sham) version. During the session, researchers used eye tracking to monitor emotional responses and collected saliva samples to measure oxytocin levels, a hormone linked to social bonding. The results showed that oxytocin levels significantly increased only after real vagus nerve stimulation, not the sham. This suggests that stimulating the vagus nerve—whether through deep pressure in the neck or shoulders, deep breathing, or similar methods—may enhance social connection. It brings to mind how primates groom one another or how animals carry their young by the scruff of the neck, simple physical actions that may be deeply tied to calming and bonding through vagal and oxytocin pathways.

Conclusion

All in all, vagus nerve stimulation and oxytocin work independently but concurrently towards common goals such as stress regulation, reduced anxiety, and prosocial behavior. All of these common goals are highly important while we students navigate college. As an upcoming senior (AL), I know all about being overcome with anxiety and stress, juggling the academic pressure that comes with learning, in addition to the expectations we set upon ourselves. This sentiment seems to almost be a universal experience, something that we all share as students who aspire to grow, learn, and perhaps achieve great things along the way. Mechanisms like VNS and the OT system push us closer to those goals, and in a more relaxed, open, and enthusiastic manner. We should persist in pursuing our studies, and even life, in this state– open to learning and growing. This is ultimately what allows us to live a meaningful life, full of memories that are equal parts intimidating and stimulating.